Denali Diary Part One

—into the Cannon's Mouth

An illustrated memoir of one of the boldest and most dangerous first ascents in North American climbing history, the direct ascent of the Wickersham Wall.

I was one of the men who made it.

- It was a defining moment in my life, and it shaped everything that was to come.

The memoir is written in two parts.

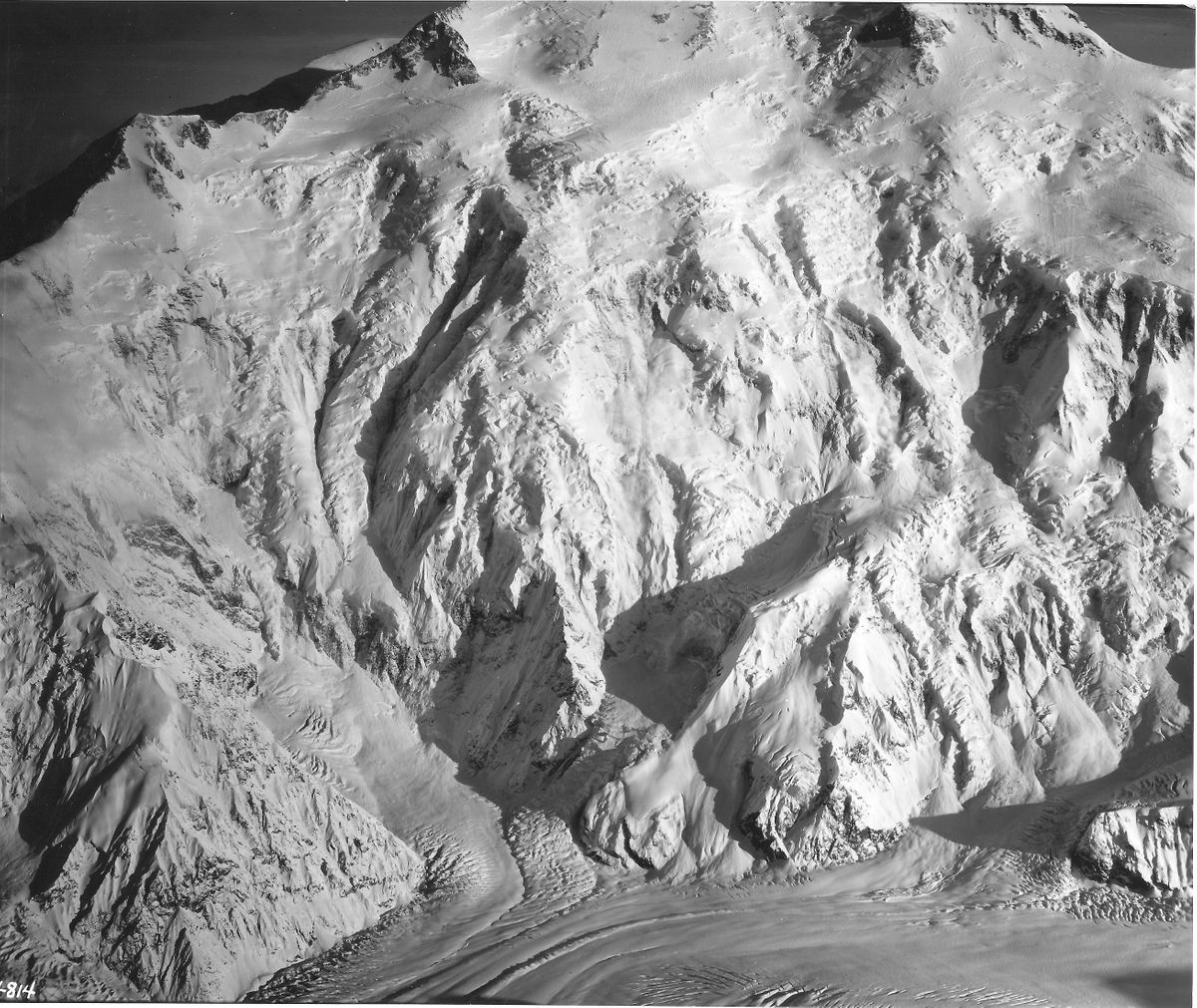

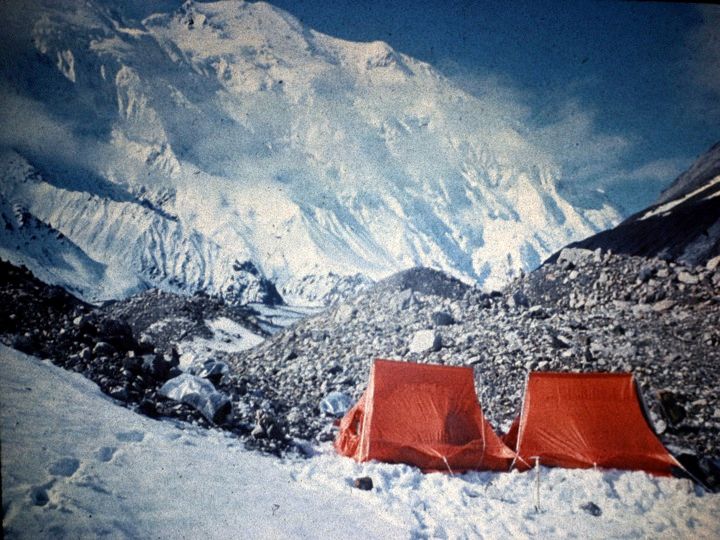

The Wickersham Wall (Bradford Washburn photo)

THE BACKSTORY

Bradford Washburn, the guy who took this amazing photo, was an accomplished mountaineer and cartographer, and the first to climb Mt. McKinley (now Denali) by what is now the standard route on the West Buttress. He became the pre-eminent expert on the huge peak, the tallest in North America, and the detailed photographs and maps he created have guided climbers there for decades. As head of Boston’s Museum of Science in the early 1960’s,he was one of America’s most accomplished explorers, photographers, and cartographers. He was also an informal mentor to the Harvard Mountaineering Club (HMC), a bunch of young, gung-ho climbers looking for challenge and adventure.

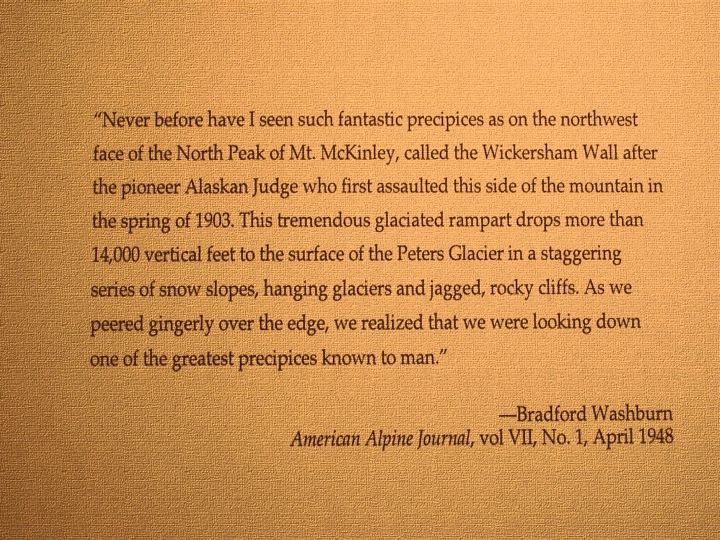

Washburn was consumed with Denali until the day he died in 2007, and with the possibilities for new, creative routes up one of the most difficult and dangerous mountains on the planet. Into the 1960s, he was particularly interested in finding a way up Denali’s fearsome, unclimbed, two-mile high, north face, called the Wickersham Wall, which was higher, bottom to top, than anything on Everest.

No climbers had ever even seriously attempted the climb, not so much because of technical and logistic difficulties, which were substantial, but because of the constant avalanches that swept down the Wall, making any attempt to climb it “suicidal”—or so said plenty of experienced alpinists. In 1963 the Wickersham Wall was unclimbed, pristine, inviolable. Washburn, however, pressed the idea that the right team of tough and intrepid climbers could conquer the Wall and return to tell the tale. And he thought he had the secret to how they could pull it off.

In the fall of 1962, he had invited three HMC leaders—Hank Abrons, Rick Millikan and Dave Roberts‑—to his home in Cambridge to hear him out. I wasn’t there, but I can picture those three friends filing into Washburn’s map-strewn study as if it were a church, which in a way it was to climbers, a sanctum sanctorum of North American mountaineering.

Washburn laid out on a large map table an overlapping series of incredibly detailed photographs he’d taken of the Wickersham Wall. The steep rock and ice faces were obvious, as were the long chutes that channeled massive avalanches falling from ice cliffs at 14,000 feet. Above those cliffs both the steepness and the avalanche danger lessened, leading to a fairly easy 50-degree snow slope to the North Summit. The problem was getting to the easy part.

Others had seen this same view from other photographs. But Washburn’s photos were stereoscopic, meaning that with special glasses there was a 3-D quality to them, making the rock and ice ridges and cliffs stand out in a way that ordinary photographs did not show.

Washburn pointed out to the three young climbers that his stereo photographs showed a shallow buttress going straight up the center of the Wall from bottom to top, sticking out from the Wall just enough, he said, that avalanches would bounce off it to the left or right on their thunderous journey down to avalanche bowls at the mountain’s base. His theory, of course, would have to be tested by direct observation, but he was confident enough to suggest that the Club mount an expedition to climb the Wall the following summer.

The three listeners didn’t hesitate. To young climbers, Washburn was a god. He knew more about Mt. McKinley than anyone. He himself had taken the photographs in question and had pioneered the use of stereoscopic photography. If he said it could be done, then it could be done. And if the HMC mounted an expedition—and succeeded—it would be one of the damndest things ever achieved in mountaineering. The perfect challenge to a bunch of very young, very competitive climbers.

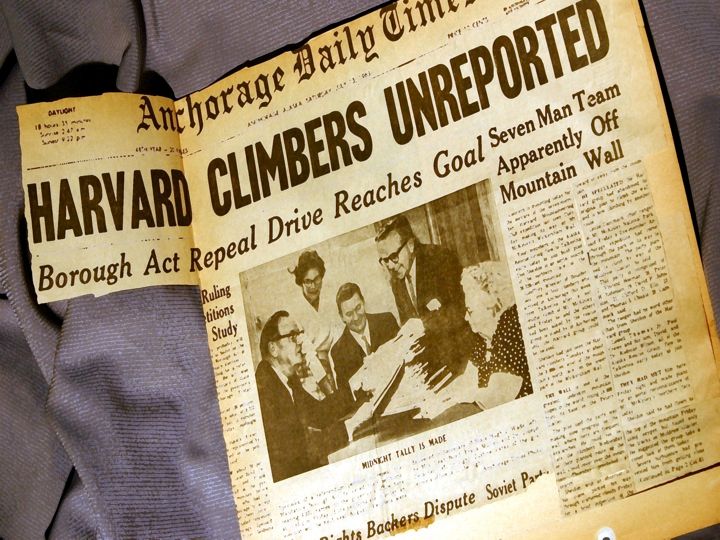

When Hank, Dave and Rick relayed Washburn’s proposal to the rest of the Club, there wasn’t a single dissenting voice. We were young. We were fearless. We couldn’t possibly fail. Or get hurt. Or die. (Many others did not share our optimism. When we were trapped for five days in a storm at 19,000 without a radio, bush pilots reported us missing, prompting a national media frenzy that we’d been swept to our deaths. We surprised a lot of people when those same pilots spotted our tents. We had no idea of the fuss until we got back down.)

When Hank, Dave and Rick asked me to join the expedition, I was ecstatic. I was a relatively inexperienced climber but, at 6’4” and in top shape from rowing crew, I could haul heavy loads up steep faces and do it all day long (my Club-mates had nicknamed me “the Moose”). Now I was going to help conquer the Wickersham Wall. Washburn had to be right, and we were going to make history. Never mind the possible falls, notoriously vicious weather, the avalanches and rockfalls that continually swept the Wall, scouring everything in their paths. We’d go up the one narrow route snaking up the center, the path Washburn marked out on his photos. Washburn had to be right.

In fact, it turned out that Washburn was at least partially wrong. We succeeded, despite the fact that his photos had missed a key feature that made climbing the Wall just about as risky as other experts had said—something we did not see until we got to the base of the climb. His protective buttress turned out to be unclimbable at its base, forcing us to defy the avalanches by climbing up an icefall directly into a large bowl into which the avalanches fell, then dashing to a protective cliff off to the left.

To improve our odds, when we got to Base Camp on the mountain, we spent two days carefully timing the avalanches, discovering that they were most likely to fall in the morning just after the sun hit the ice cliffs at 14,000 feet, loosening the huge blocks—and again in the afternoon when the ice re-froze and expanded. Armed with this information we timed our trips up the icefall to minimize getting hit by the next massive, roaring onslaught of ice and snow.

We climbed that icefall not once but seven times, daring the avalanches to hit us, carrying all the food and gear we needed for the vertical two miles of climbing ahead. Each time we found our tracks from the previous trip buried under tons of avalanche debris. Our avalanche prediction system was not infallible, and no doubt the sensible thing to do would have been to stop playing Russian Roulette with the avalanches and go home. But that never occurred to us.

Washburn’s photos were still a useful guide, but pure luck had as much to do with our climbing that unclimbable Wall and living to talk about it. We not only did that epic climb but also made the first traverse of the mountain—up the Wickersham Wall to the North Summit, across to the South Summit, then down the West Buttress. 38 days. Without a scratch.

In 60 years, the “Harvard Route” still has not been repeated. At least one climber—a friend and colleague named Chris Kerrebock—has died trying, wedged upside down in a deep crevasse in the Peters Glacier until he froze. He and his partner hadn’t even made it to the base of the climb before Denali defeated them. Even without the awful image of Chris slowly freezing to death, the extreme dangers of the climb have made it a “don’t even consider” for the global climbing community. There may never be another attempt.

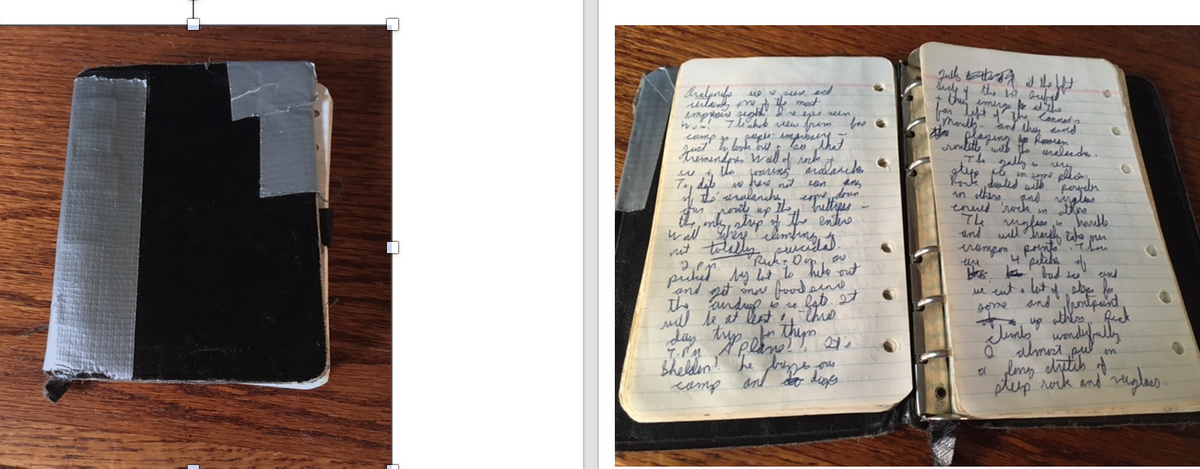

I’m telling the story now, because of three powerful prompts. The first is my discovery of the diary I kept on that climb. For decades I‘d forgotten it existed. Reading it over, I loved the passion, exuberance and irreverence I found in it and resolved to use those unedited words, in all their raw clumsiness, as the spine of a new story of the climb. I’d add just enough new language to provide context and connections where needed.

Almost at the same time I discovered the diary, I also found a trove of black-and-white photographs I’d taken on the climb that had somehow escaped notice and lain in a drawer as prints and strips of negatives for half a century. Some of them are quite spectacular so I added them to the color images I already had. The editors of Ascent, a prestigious mountaineering annual, considered some of these shots important enough to feature in its 2021 edition.

And the final nudge to get busy writing is the passage of time. Three of the seven of us are dead and the rest of us are in our early 80s. It’s time to do something about the missing elements of our story that need telling. Read on....

THE ADVENTURE BEGINS

(COMMENT: The diary words are in black; any parts of the narrative not from the diary are in blue. Some of these are paragraphs from other journals or from my memoir, Quest, I've also added explanations of terms that may be unfamiliar to the reader. And in a few places I've inserted present day additions where I felt that, for whatever reason, the diary missed or simply did not do justice to what had really happened.

CHAPTER ONE: North to Alaska

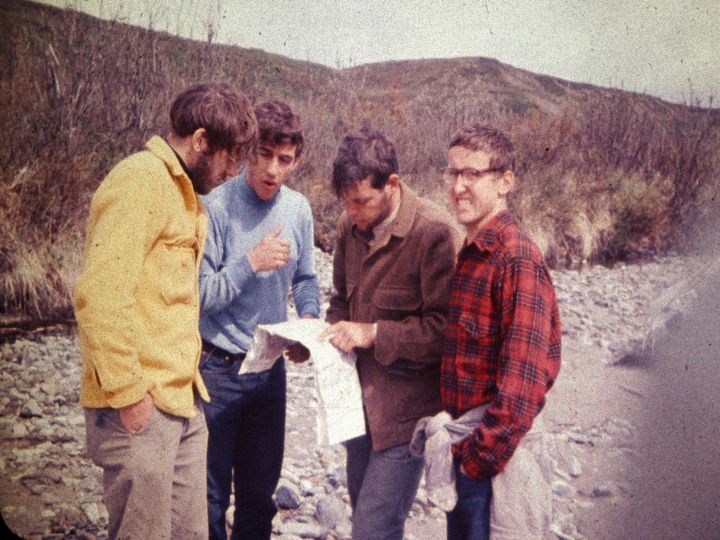

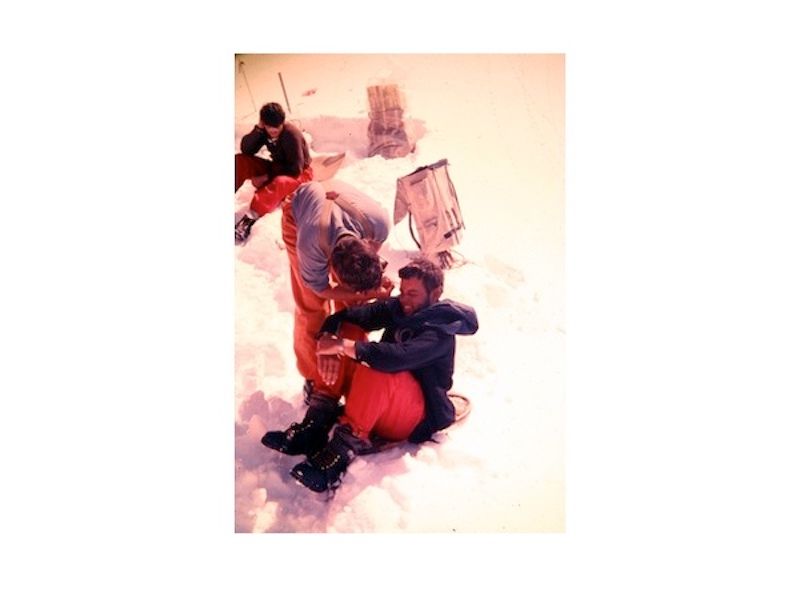

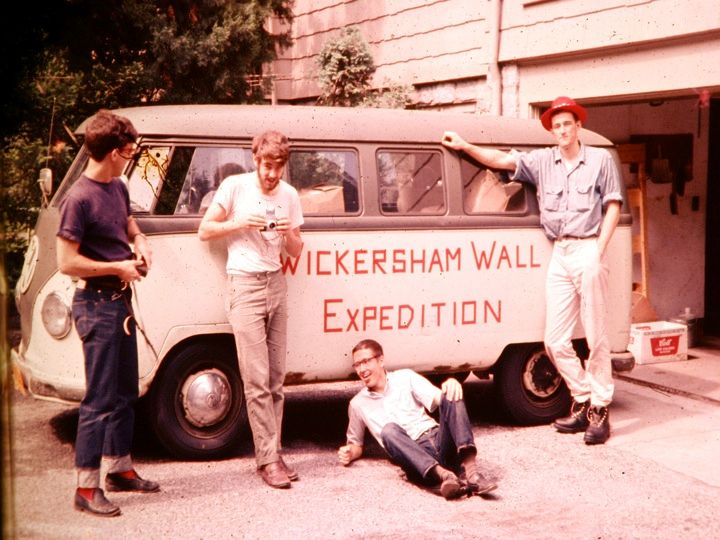

Scarsdale, NY June 8 1963: Hank Abrons, Rick Millikan, Dave Roberts and me. Not shown: Chris Goetze, Pete Carman and Don Jenson

The Team

Hank Abrons was headed for med school in the fall and packed our medical kit. He said we needed a bone-saw in case of a gangrened leg. Ugh.

Rick Millikan had the right credentials; he’s the grandson of George Leigh Malory, the famed Everest explorer.

Dave Roberts would become one of Americans foremost mountaineering and adventure writers.

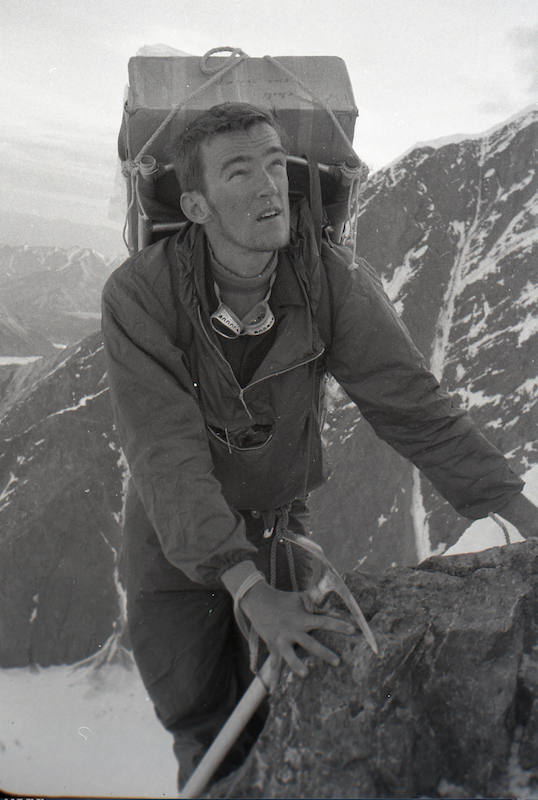

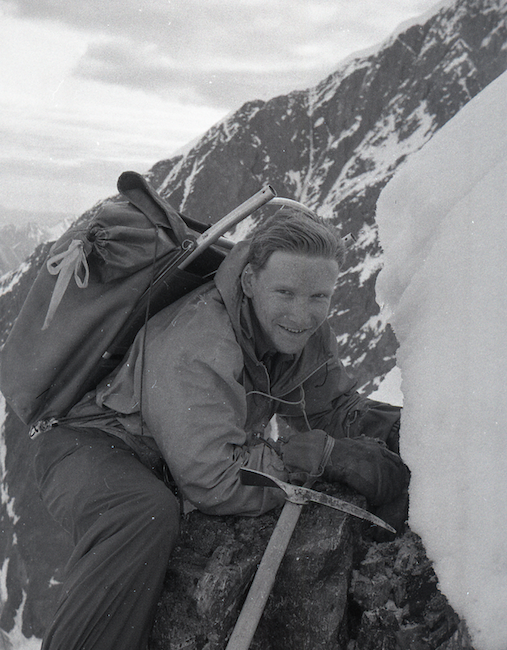

John Graham. At 6’4," I was the biggest guy on the expedition.

Chis Goetze, the only grad student in the group, designed and made all of our tents, which stood up to everything Denali could throw at them.

Pete Carman was famous for the loud ties he wore on the toughest climbs.

Don Jensen even then was making a name for himself as a mountaineering equipment designer.

Me, Chris Goetze, Hank Abrons, Dave Roberts and Rick Millikan

- June 2 [1963]—Cambridge.

- Pete left for Alaska. Will pick up Don on the way.

- Dave left for Scarsdale.

- June 4—Cambridge.

- Dave returned to pick up me and Rick.

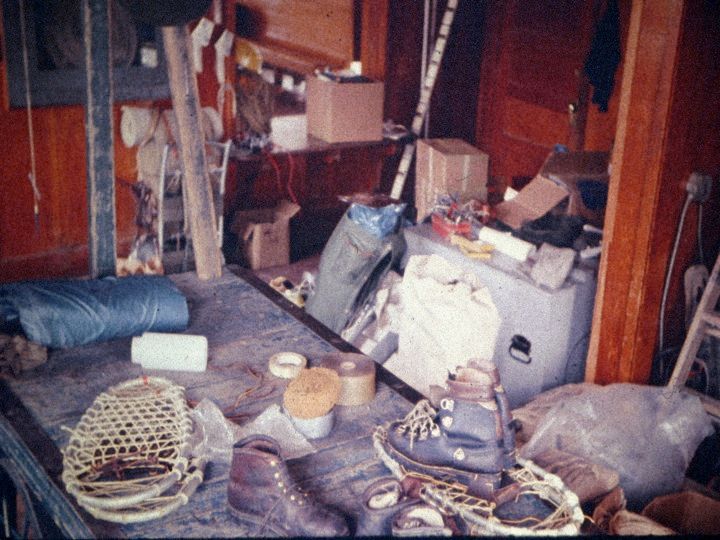

- June 4-7—Scarsdale.

- Packing. Food is broken down into Pack-in, Base Camp, Low Altitude and High Altitude. All but Base Camp food is packed in meal-sized servings. Takes a lot of measuring and millions of plastic bags. We get two or three days food for seven into a small carton. Freeze-dried meals for high altitudes really cut weight.

Tents are checked and wands painted. Fixed ropes are cut. Medical kit is packed.

We’d made the tents ourselves. We cut the aluminum snow pickets from what we found in a hardware store [the pickets were meant to hold falls on steep snow slopes]. We painted garden store bamboo wands to mark our paths in inevitable white-outs. We made our own snow shoes by bending aluminum tubing and adding nylon webbing stiffened with spar varnish. A lot of our personal gear was from Army surplus. About the only things we had to splurge on were Eddie Bauer down sleeping bags and Peter Limmer custom-made boots.

Everything is pretty well organized and packed by midnight on the 7th.

- June 8—en route to Alaska

- Left Scarsdale at 10:00 AM. Odometer mile 55,360.

- Never thought we’d be done packing. Took photos of ourselves and the bus. Took the turnpike towards Chicago. Ran out of gas in central Pennsylvania.

- June 9

- Driving without stop past Chicago.

- .

- June 10

- 3:00 AM Fargo ND. Noon in Minot.

No trouble at the border with customs although I think the guy was a little bit skeptical that we’d make it up the Al-Can in that bus. I drove from 7-12 over flat Saskatchewan farmland. Road straight as a string. Didn’t stop until after ten PM.

- June 11

- In Edmonton at 9:00 AM. Dawson Creek 9:00 PM . Beginning of the Al-Can Highway. Hit the gravel at mile 83. Tough driving. Mud everywhere. Battery gave out at about 2 AM. Low on fluids. We used water from a teakettle to get the bus to work again.

- June 12

- On the Al-Can. Not so much mud now. Lots of dust. Road in good condition. We’re making over 600 miles per 24 hours on it. Scenery is rapidly improving and we are starting to see big mountains. Prices rise as we go. Into the Yukon by 11PM. Tonight there is no night. The light only dims for a few hours.

On the Al-Can Highway June 12. Dave Roberts and me.

- June 13

- Scenery really superb. Rushing streams, clear mountain lakes, peaks, and big game. In Whitehorse at 9 AM. Got a flat tire in the afternoon. People up here are tough, just as tough and taciturn as the land in which they live.

Curious. June 13, 1963 was my 21st birthday. But there is no mention at all in my diary of any celebration or even notice. I guess I did not mention it to my friends who would have certainly done something. But why did I not tell them? A half-century later, I have no idea.

- June 14

- In Anchorage at 7:00 PM. Six days from New York. We put up at a motel and start checking out the gear. Pete and Don are already at McKinley Park. Bad news. Another party is climbing on the north side of McKinley right now but it seems that their route is far off to the right of the Wall proper. But the bastards have taken the 2-way radio that had been reserved for us.

- June 15—Anchorage

- In Anchorage. Run errands, repack gear. Rest up. Weather still very overcast. Haven’t seen McKinley yet.

- June 16—McKinley Park

- Left Anchorage under overcast skies. Is there such a thing as a blue sky in Alaska? Drive north and then west on the Denali Highway, a dirt road which winds over the tundra. What tremendous scenery! Range after range of tremendous peaks. Never have I seen mountains like these. It's wild country. Moose, grizzlies, caribou, rabbits. The tundra is barren and foreboding. We’ve descended a bit and made McKinley Park at midnight and camped out in the rain. Rain. Rain. Rain.

- June 17—McKinley Park

- Railroad Stationmaster let us stay in the station to cook and to sort our gear for the airdrops. Bush pilot Don Sheldon is set to make our air drop of food and gear into Base Camp on the 22nd. Pete will wait for Chris (Goetze) who is finishing some Army Reserve training in Alaska and the two of them will start in to Base Camp on the 27th. We’re lucky to find this kind stationmaster—the hotel had kicked us out of their lobby. Plenty of tourists come in on the train and a bus takes them out to see the countryside.

Sorting gear in McKinley Park. We made the snowshoes ourselves, from stuff bought in a hardware store.

CHAPTER TWO: BASE CAMP

June 18—pack-in

Five of us left McKinley Park at 5 PM. Drove down near Eielson, talked to a ranger at Toclats about the river crossing. He advised us to take the long route in over Gunsight Pass because of treacherous fording further down. Went toward Wonder Lake. Out first view of Denali was a tremendous experience. First a high peak poked through the clouds. “That’s it! That’s it!” we all shouted. Then a ridge was seen growing even further up into the sky. Then, unbelievably, the North Summit appeared above everything, way, way above the low cloud layer.

I don’t believe it. Jesus Christ. Can anything be that big? It is huge. Unbelievably huge.

Carman sees the mountain first

We stop and park about five miles short of Wonder Lake. The sun goes down on McKinley at 11:30 PM. It is still very light. We can take pictures. We head for the McKinley River through scrub and sparse spruce forest. We are at the river at 1:20 AM.

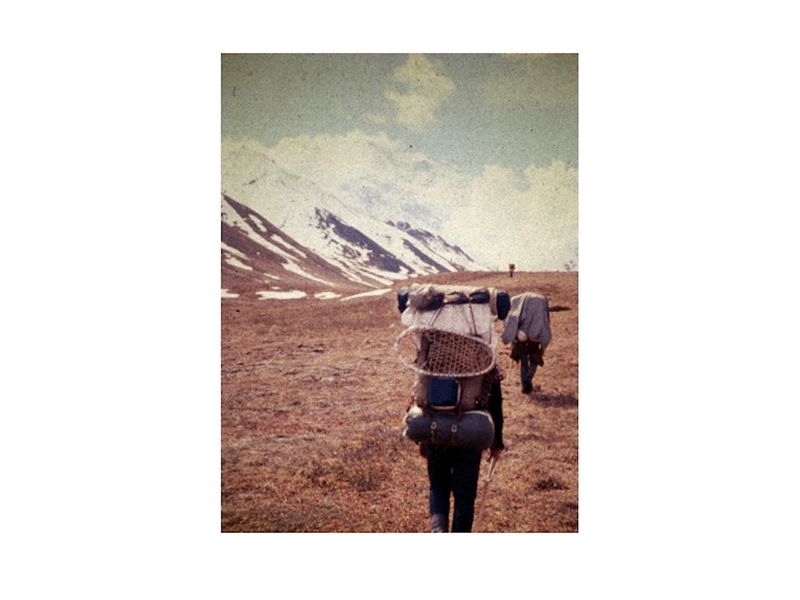

June 19—pack-in

We begin fording. It’s difficult but not impossible. The rangers don’t know what they’re talking about. The river is about a mile and a half wide, in 8-10 braided channels. The water averages one foot in depth with a maximum of two feet. We cross it in an hour.

1:50 AM sunrise on McKinley is quite a sight. We pad [go to sleep on our Ensolite rubber pads] on the far bank. Clear skies. The crossing was a fine adventure and a great start.

8:30 AM—we hoist up our 75-pound packs and set out. The going was not too bad. We did hit bad patches of muskeg [a kind of peat bog with treacherous footing] and these areas were tough. We tried to follow the game trails but even so we occasionally had to fight our way through very thick underbrush. We are moving pretty well, however. We take compass bearings and follow them out. About 12 we hit Clearwater Creek. This was the toughest crossing of the trip so far. One bad channel put a good scare into all of us before we were safely across it. It would have been bad to slip. Lunch in the rain, ponchos on.

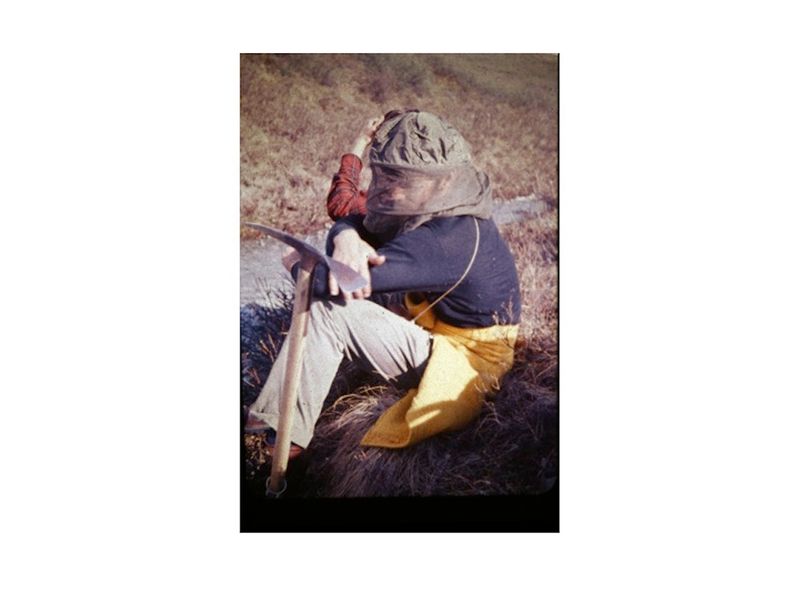

After lunch the rain stops and we push on. We find an easy ford at Carlson Creek. We are getting pretty bushed and at five PM we stop by a creek bed about six miles from the snout of the Peters Glacier and camp. McKinley looks even more incredibly huge. Mosquitoes getting very thick but repellents and head nets do a good job. Had a great glop* meal by the stream. Smoked a cigar. Dave felt lonesome for classical music so Hank and Rick attempted some Mozart on their harmonicas. Beautiful view of the mountain.

*Translation: "glop" refers to the one-pot meals we ate for most of the expedition. Lower down these consisted mostly of rice and some kind of tinned protein and perhaps cheese. Higher up we ate lower-weight freeze-dried meals.

June 20 —pack-in

Up and at ‘em. It rains off and on all day long. About 3 PM starts a steady downpour. Pretty darn miserable, hiking in ponchos. We pack over some muskeg but the going is generally pretty good and we move well. About 5 we are at the edge of the Peters Glacier. The moraine is terrible hiking—it’s wet serpentine (a slippery rock). We get onto the Peters and pitch our tents on a snow patch. So far, our plastic rain flies are keeping the pelting rain out. Hope they will continue to do so.

June 21—Base Camp, 5,350’

Get off late and started up the Peters. Temperature is 48 at 10 AM. High cirrus, then socked in for most of the rest of the day. Some of the moraines provided pretty tricky going. We encountered huge crevasses and one very large ice cavern. Got to the site for our base camp at 5 PM and set the tents solidly. Base camp snow is 1 to 1 and 1/2 feet deep and very wet. Most everybody’s feet got very wet coming in. Weather clears in the evening. We are right under the Wall now and can do a lot a visual route-finding.

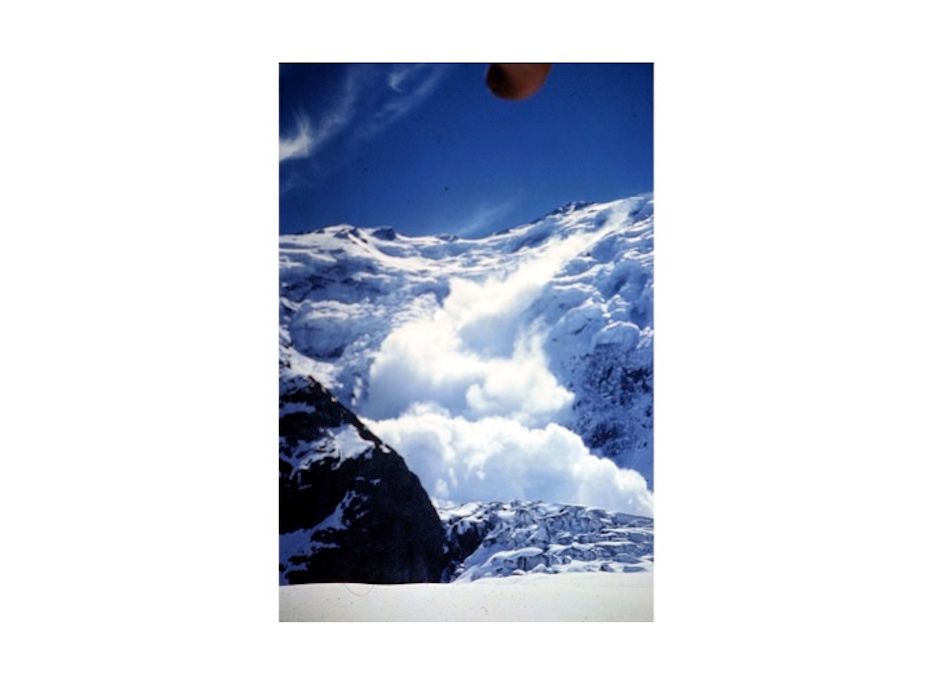

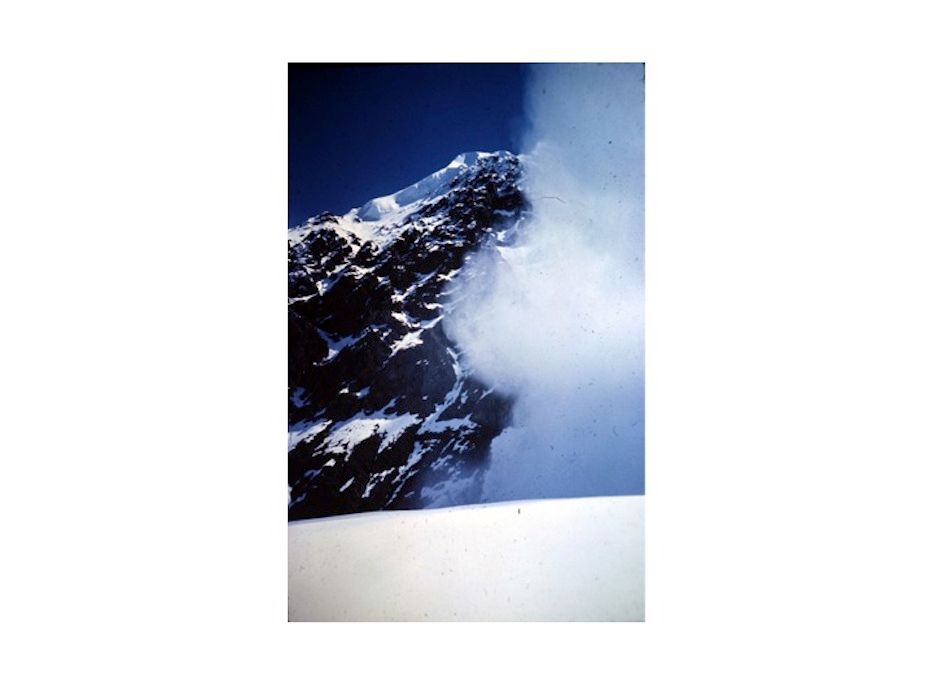

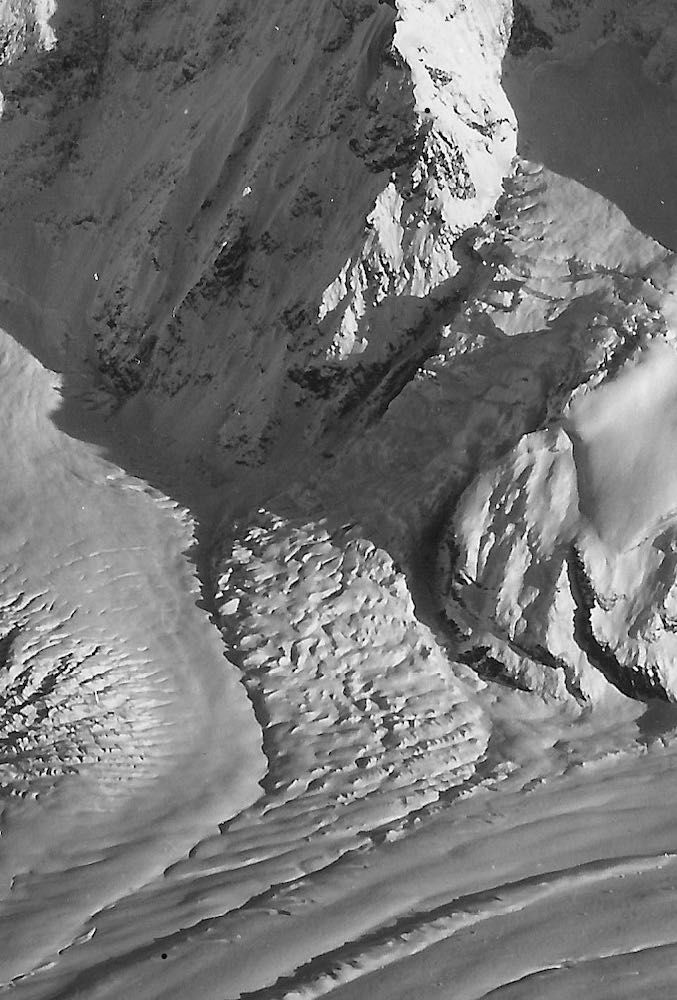

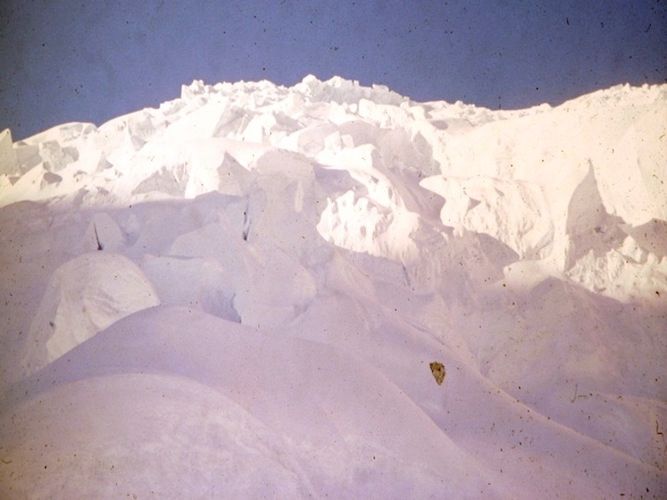

Bottom of route: Icefall in center; rock and ice gully to its left; rock ridge top center; avalanche bowl ("Cannon's Mouth") top right

Bradford Washburn photo

June 22—Base Camp

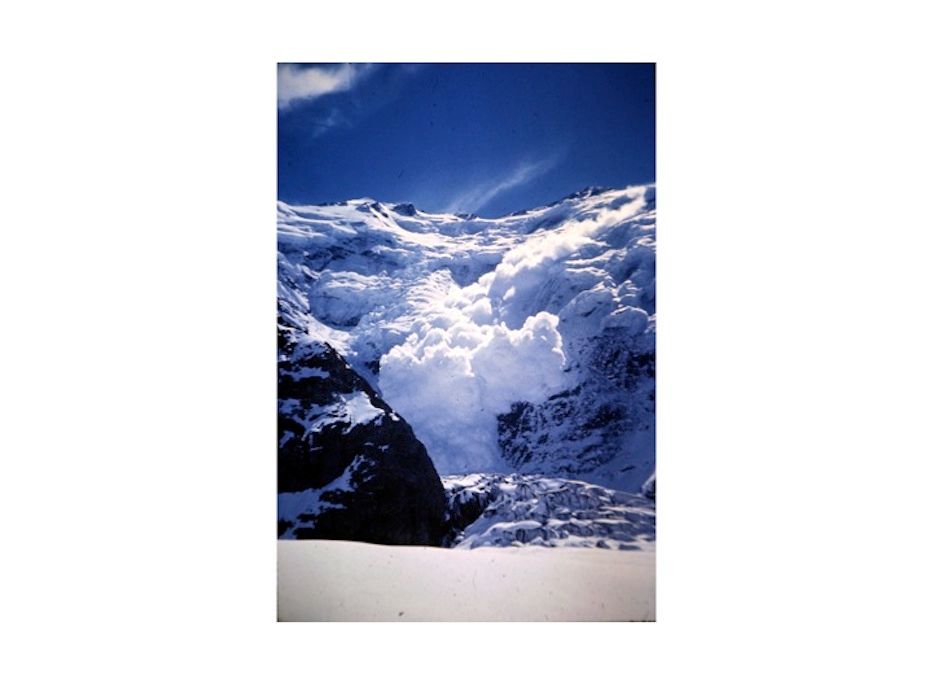

Heard a big roar during dinner and rushed out in time to see a huge avalanche breaking off from ice cliffs high above and roaring down the Wall. Gave us some food for thought. By 9, two smaller avalanches have also fallen. Rick and I are driving the others batty with off-key Kingston Trio.

Avalanches heard steadily all through the night and day. The shock waves from some of them shook the tent. We will be damn lucky to make this climb in one piece. The Wall is shedding almost continually. It takes 45 seconds for an avalanche, breaking off ice cliffs at 14,000', to fall nearly two vertical miles.

Totally socked in today with snow and whiteout. No airdrop. Spend the whole day in the tents playing word games and poker dice. At 9PM the weather turns colder and the snow is not so wet. There is a steady roar of avalanches. Six inches to one foot of new snow. We start rationing food.

Alamy photo

The image above is an Alamy photo of avalanches crashing down either side of what would become the "Harvard Route." The sights and sounds of them crashing past just to the left or right was awesome. But to the extent we could stay on that shallow buttress, the main avalanche danger was from brief blizzards of flying ice and snow. The problem was that the bottom part of that buttress proved unclimbable, leaving us no choice but to climb straight up into the avalanche chute to the right in this picture.

CHAPTER THREE: INTO THE CANNON'S MOUTH

June 23—Base Camp

Morning fairly clear, Rick, Dave and I go out to snowshoe out an airdrop site [for bush plot Don Sheldon]. All wet things are brought out and dried in the sun. All of us lay around and play poker dice on Ensolite pads in the snow. Weather starts to deteriorate about noon and we retreat inside the tents. No airdrop. We are on two meals a day to stretch the food.

The icefall and the Cannon's Mouth

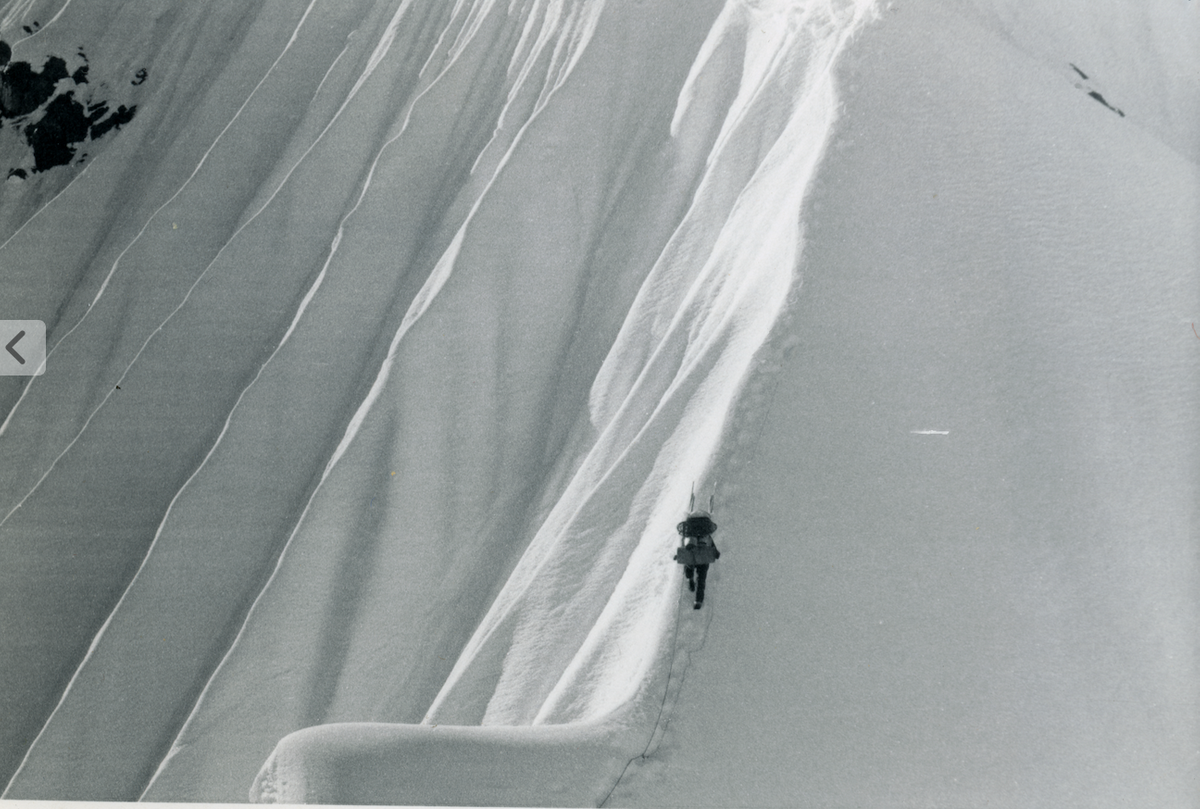

We did get several hours of good observation of our route. Our buttress is the only part of the Wall not continually swept by the big avalanches. Only some snow avalanches have come down it. But we find to our concern that the buttress ends 1500 feet above the Peters Glacier. So our big sweat is that first 1500 feet.

Our first option is go up an easily climbable but exposed icefall that rises 1200' from the glacier. On top of it is a bowl which catches the big avalanches. We must cross this bowl, then climb a steep rock rib to its left to reach the beginning of our route up the buttress. It will take perhaps 20 minutes a trip to cross the bowl and if any poor SOB is hit then with an avalanche, ain’t heaven or hell can save him. We hope this is the most dangerous spot of the climb. We can’t tell much about the high ice from here. The technical difficulties are, we feel, all surmountable. If the weather and the avalanches only give us a break we can do it.

All through dinner we hear the roar of avalanches. They never stop. What a face the Wickersham Wall appears from here! What a feat if we can climb it! Damn bad weather. Still snowing.

June 24—Base Camp

Morning dawns bright. Only puffy clouds here and there. Don and I go out and re-stomp the airdrop site. All of us lay around on our pads playing poker dice. Our two meals a day keep us fed, but a mite hungry.

Sheldon does not show. Weather begins to deteriorate. Rick and I rope up and go up to reconnoiter the first part of the icefall on snowshoes. We go about 400 feet up it—enough to see that it is pretty easy going. We are where no one has ever been before. No avalanches fall during the hour or so we are up there. We do encounter small crevasses. We return and Dave and I serve up another glop for dinner. Afterwards it is decided by lot that Don and Rick will hike out for more food tomorrow if the weather is not really promising.

Dave and Hank will leave tonight to put the route up the rest of the icefall and into the bowl. All through the evening avalanches crash like mortars.

On the lower part of the Wall we will climb at night and sleep during the day. "Night" this far north consists of a twilight about midnight and a sunrise at 2:30 AM. Still, the air is colder at night, the snow is harder and easier to climb on and the avalanches are less likely to fall with some ice "glue" holding them back. Above about 12,000 feet we will revert to daytime climbing because the air is colder and the snow harder.

At 10 PM all hell comes down the face and into the bowl above the icefall and over the lip. The cloud sweeps to the bottom of the icefall and three minutes later the shock wave shakes our tents. Thank God it went off before Hank and Dave were in the bowl. Would have been really bad. Big problems are encountered even if you are not reached by the snow—the fast-moving avalanche cloud can suffocate a person easily. We all hope Sheldon will drop tomorrow. The SOB has had two good mornings and not shown.

June 25—Into the Cannon’s Mouth

Hank and Dave snowshoed to the top of the icefall, to the avalanche bowl which we have christened the Cannon’s Mouth. They went clear across the bowl from right to left and returned before starting down. Their route up the icefall is fairly well-protected against falls and crevasses. The only difficulty is the fifteen-minute crossing of the bowl. Dave reports that the bowl is filled with huge chunks of avalanche debris and “looks like a battlefield,” as does the top part of most of the icefall. If we take this route it will mean that for fifteen minutes each way, each trip we will expose ourselves with no hope of protection to the super-avalanches which thunder over the bowl. About one super-avalanche seems to fall every day, plus dozens of regular avalanches. There would be little hope for anybody caught in the bowl. It would be like being hit by a swarm of express trains. Hank and Dave return about 4:30 AM. At six and at seven two super-avalanches fall and the shock waves shake our tent.

Morning—weather fairly good. No airdrop. At eleven, all of us are laying around on our Ensolite pads in the sun, playing poker dice. We hear the familiar roar of an avalanche and look up. Way above, at 14,000’, just to the left of our route, a big avalanche is building speed. It looks really big. Dave runs for his camera. The avalanche takes about twenty seconds before it reaches the top of what we've named the "Eiger Face," the rock face to the left of the bottom of our route. Then it crashes into its bowl with a huge roar. It’s still coming! Now we are alarmed. The avalanche cloud rises, expands and blots out the sun. We are a half-mile away but the cloud is upon us in seconds. In a second we are in the middle of a howling blizzard. Three minutes later the cloud has passed and we are covered with snow and cursing. It is the biggest avalanche we’ve seen and certainly one of the most impressive sights I’ve ever seen. Wow! The whole view from base camp is super-impressive—just to look out and see that tremendous wall of rock and ice and the roaring avalanches.

To date we have not seen any of the avalanches come down our route up the buttress—the only strip of the entire Wall where climbing is not totally suicidal.

2 PM. Rick and Don are picked by lot to hike out and get more food from our van since the airdrop is so late. It will be at least a three-day trip for them.

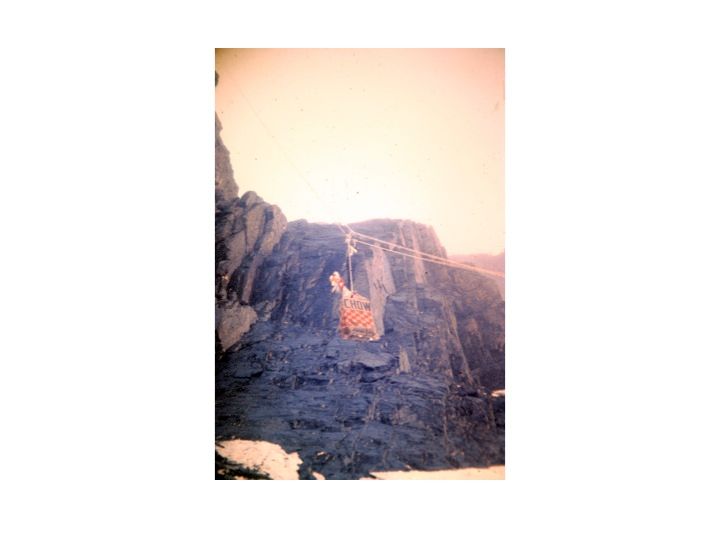

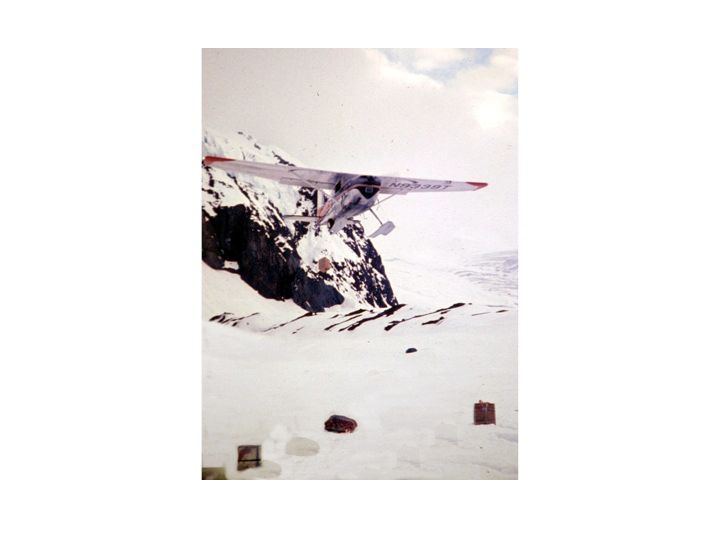

4 PM. A plane! It’s Sheldon! He buzzes our camp and drops a tin of food and a message wishing us luck and saying he’s got some frostbite cases but will drop in six hours. Hooray!

6 PM. Rick and Don, having seen the plane, return.

8 PM. Sheldon returns. We run up to our pre-arranged drop site but no! he starts dropping only feet from our tents. What a flyer! He comes in at about 30 feet and each box drops within a 30-foot diameter circle. We wave and shout and take pictures. He drops half the stuff.

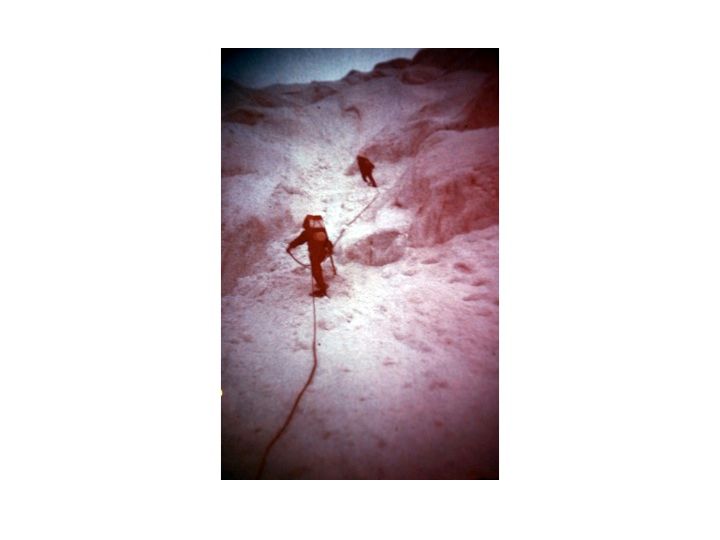

10:30 PM. Rick and I rise and get on our climbing gear. Given the danger of climbing straight up into an avalanche chute, we will try to put an alternative route up a steep gully to the left of the icefall which emerges at the far left of the Cannon’s Mouth. This will lessen playing Russian roulette with the avalanches.

The gully is very steep ice in some places, rock dusted with powder in others and verglas [ice]-covered rock in others. The verglas is horrible and will hardly take our crampon points. There are four pitches of bad ice and we cut a lot of steps for some and frontpoint up the others. Rick climbs wonderfully and I almost peel on a long stretch of steep rock and verglas. Near the top we must climb under hotel-sized overhanging seracs [unstable towers of ice]. The night is warm and it had been snowing lightly and the icefall creaks and groans. So do the seracs. Brrr! We reach the top of the gully and go up one more pitch on rotten rock. It is obvious now that we cannot pack up this route. It is technically difficult and the seracs and lots of treacherous loose snow don’t make it much safer than Hank and Dave's snowshoe route.

Rick and I start to downclimb. The snow has stopped and the rising sun (2:30 AM) and the clouds and the glaciers and peaks to the north are absolutely spectacular. And we neglected to bring a camera! We downclimb swiftly, mostly front-pointing. No mishaps, which is good because there is hardly a spot for a good belay.

June 26—Up

4:00 AM, Rick and I return.

5:30 AM Sheldon returns and Pete is with him to throw out the rest of our food and also a letter saying 1) Chris has arrived and 2) Gmoser—the guy whose party climbed the right edge of the north face last week—thinks we are going to our doom.

The morning is fairly clear. We sort out all the drop stuff. Everything is there except one spare case of Wylers lemonade. Sob! Most of the food boxes are in pretty good shape.

We pad for the afternoon and eat at 8:30 PM. Fried pork chops. Ummm! A real treat.

At 10:30 we get up and start buckling on our gear. The scene reminds me of a wardroom of pilots or gunners getting ready for a fight. No talk. Tonight we will go into the Cannon’s Mouth.

Hank and Don will keep going and try to establish a route up a rock rib that rises to the left of the Cannon's Mouth to a rock shelf at 7,100 feet. The rest of us will take food up and establish a cache at the left edge of the Cannon’s Mouth hopefully out of avalanche danger (6,650').

We climb the icefall by the snowshoe route, wanding our path. We cross lots of crevasses. I fall in one up to my neck but catch myself by jamming with arms and pack. We reach the Cannon’s Mouth, cross it as fast as we can and pick our way across some snow bridges to the bottom of the rock rib and make our cache (which becomes Camp I). Then we return to Base Camp.

"Wanding our path" means placing painted bamboo sticks we got in a garden store in Scarsdale in strategic places as we went up—so we could use them as guides if visibility got bad on the way back.

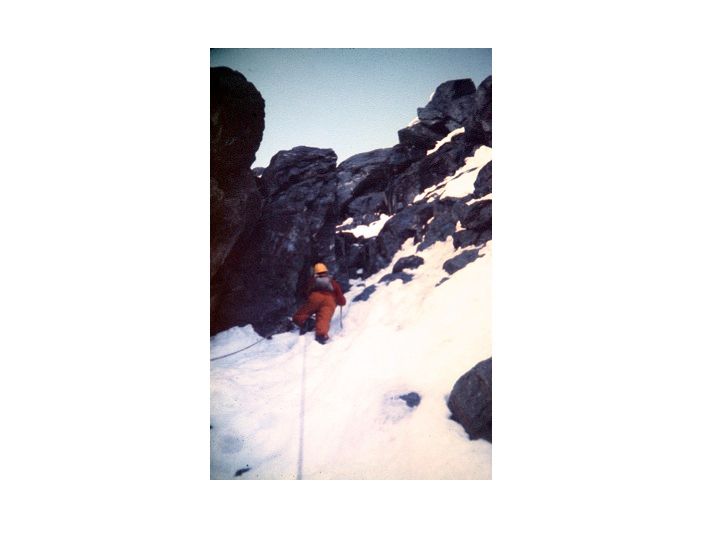

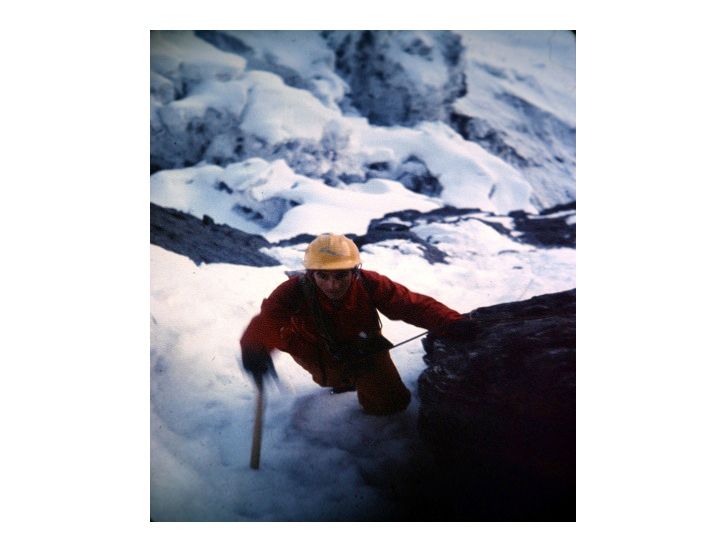

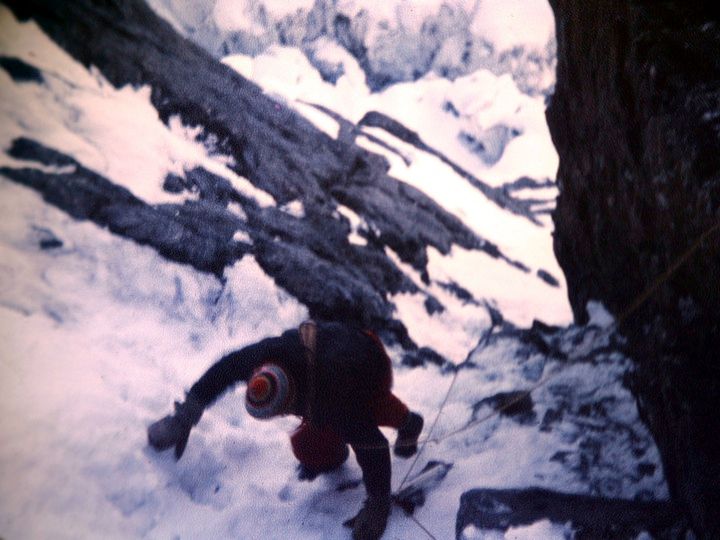

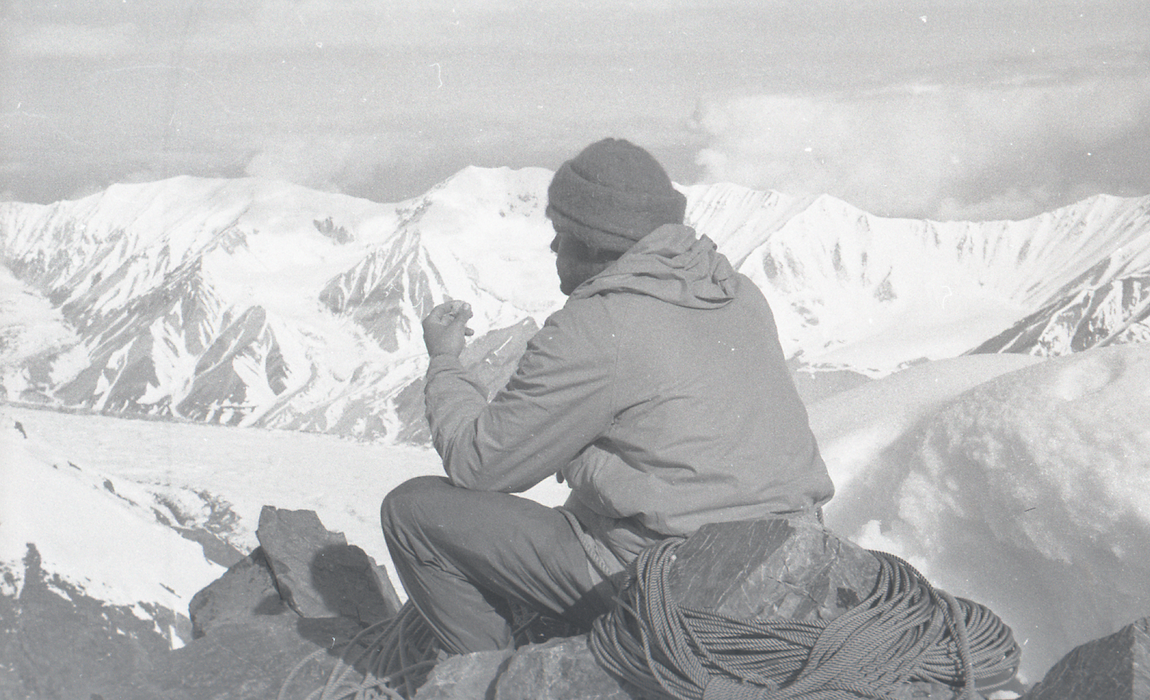

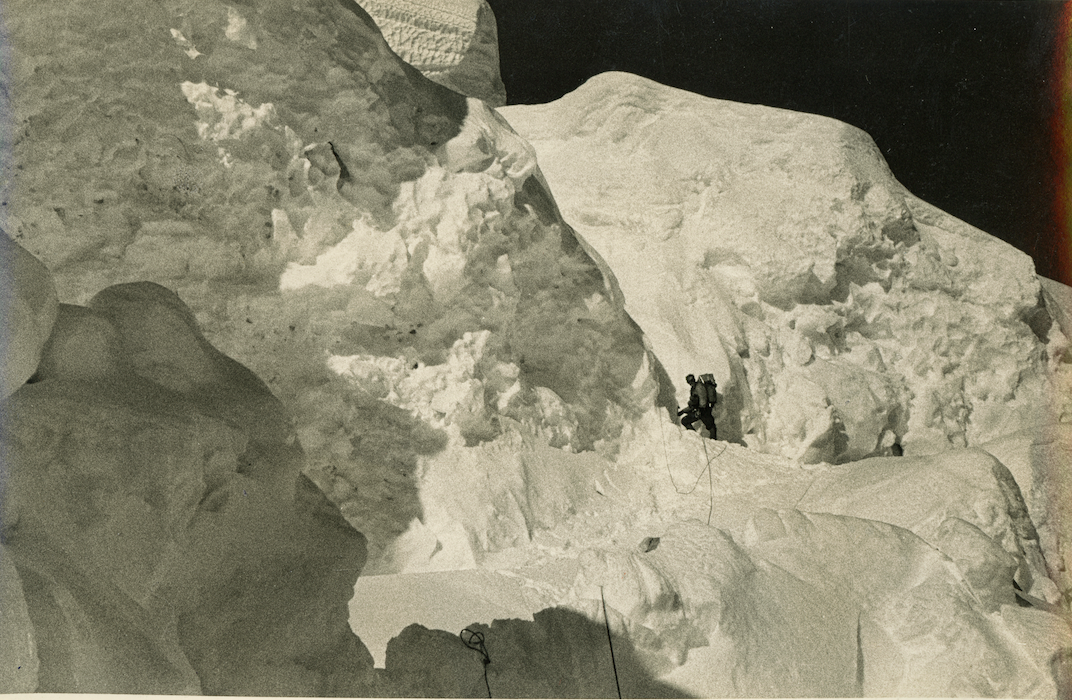

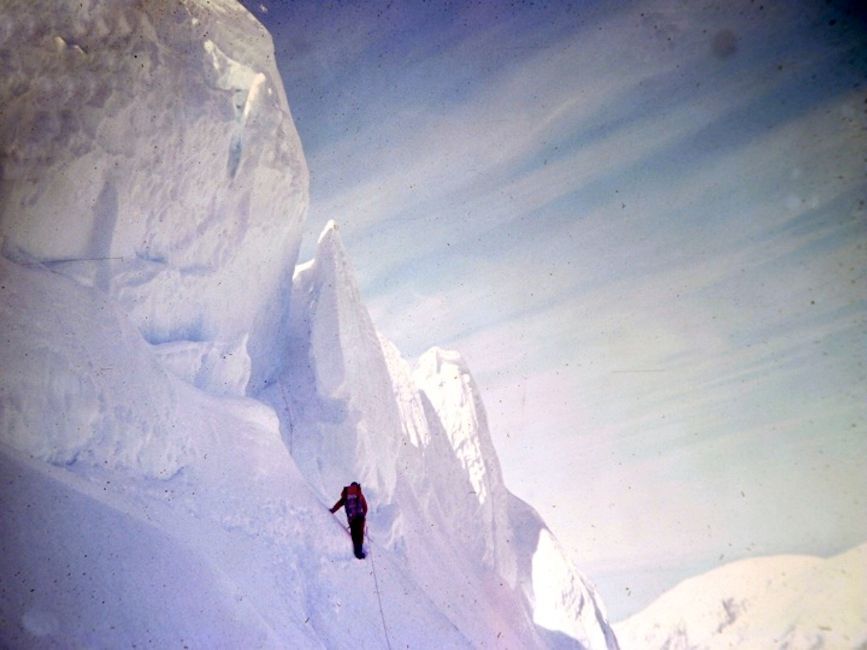

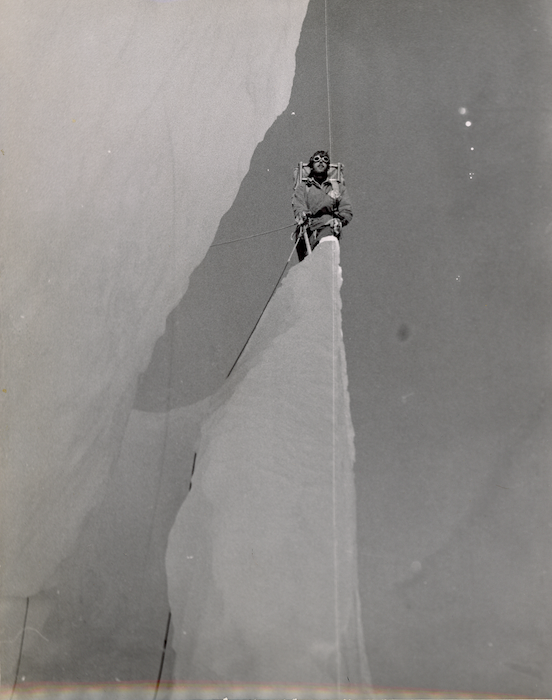

The four shots below show us climbing the icefall—straight into the Cannon's Mouth

June 27

Hank and Don return after having put the route in over the lower ¼ of the way up the rock rib that goes 450' up from the cache at Camp 1 to the rock shelf. They report that the going was tough because of rotten rock but that the route will go [i.e. is climbable]. We all eat a hearty hot breakfast and pad.

Wear a helmet? Now why would I want to do that?

Rick and I are more or less established as Base Camp cooks – which means we are two in a tent with the cooking gear. We have approximately ten days of Base Camp food but hope to leave Base Camp within five. All we have to do is haul everything to our cache at Camp 1 and finish the route up to the rock shelf (which will be Camp 2).

It will be great when we are living on the face. Even at the cache at Camp I (1,300’ above Base Camp) the scope and view are tremendous. We are now climbing at night, sleeping by day. A snowstorm starts at daybreak and continues for over 24 hours.

Did no climbing this morning due to continued warm, wet, sticky snowfall. Did nothing but play games, read and sleep all day. The storm stops in late afternoon and it becomes clear and cold. Tonight Rick and Dave go to put the route up the rest of the way to the rock shelf (7,100’). The rest of us pack loads up through the Cannon’s Mouth to Camp I.

The route description below is from Hank Abron's climbing journal. It gives you a sense of the technical moves needed to climb this steep and icy rock:

"Pitch 4: Rick continues up couloir 80 feet to beginning of steeper snow (one piton). Pitch 5: Rick leads 70 feet further up couloir to bottom of 20 foot rock band which is climbed on small face holds, then 30 feet up 55° snow to rock outcrop on the left (two pitons). Pitch six: Dave traverses around corner 20 feet to the left on 35° snow, climbs back onto rock on the waist high outsloping block with verglass (5.5), Then continues 40 feet diagonally at juncture of rock and snow to belay stance (one piton). Pitch 7: Rick leads; from a steep tongue of snow there is a difficult move balancing up to a vertical block which is surmounted by a retable [essentially doing a pushup to a head-high flatter area] (5.4), then 25 feet directly up snow to rock protrusion climbed by another retable, and 30 feet up gentler snow toward rocks on the right (one piton)."

June 28

We consider trying to get in two loads but snowshoe troubles and the late hour dissuade us. There is perhaps only 1-½ hours when the sun does not hit the hanging glaciers high on the north face. Only then can we be fairly sure that a super-avalanche will not get us. We figure that the hours for maximum safety in the Cannon’s Mouth are about one to three AM. Anything outside that is tempting fate a bit too much.

One avalanche does hit the back of the bowl as I am leading across it. It scared the hell out of us for a moment. This kind of risk is an integral part of mountaineering—and of adventure. For perhaps fifteen minutes we are thumbing our noses at the Almighty. Not much could save us if He let a Big One go at the wrong time. Crossing the Cannon’s Mouth is one of the biggest thrills I have known.

We are all getting pretty blasé about the avalanches now and do not even bother to look up anymore unless we hear them start up high.

Avalanche debris from another near miss

The terrain here is out of this world. The huge wall confronting us, the avalanche bowls, the Eiger Face to our left, the Cannon's Mouth to our right, the sunrises and sunsets—and our route, which is the one wrinkle in the massive Wickersham Wall which seems to protrude enough to deflect the deadly avalanches.

The Cannon’s Mouth is an awfully impressive sight—huge hotel-sized blocks and seracs, snow bridges, tons of avalanche debris—and the sheer ice walls behind which are the Cannon’s fuse. The Mouth itself is the apex of a funnel, which drains at least 1/3 of the Wall. It’s funny, all this ice, ice movements and exposed rock seems to be reviving my interest in geology.

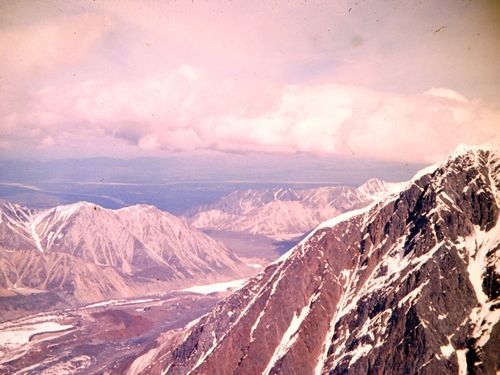

Looking east from 7,100'

The same view at sunrise

June 29

We sleep during the day. At 3:30 Pete and Chris arrive. The expedition is all together now. Weather warm and overcast. At 10, Rick, Don and Dave pack a load up to Camp 1. At 10:30 Hank and I leave with all our personal gear, tent, stove and food. We will attempt to pack up the fixed rope route that Rick and Dave set in the night before. We don’t know yet if it is feasible to take packs up that route.

The first two pitches are easy rock, with a steep snow traverse. Then follow some more difficult pitches. Pitches 4 and 5 are very high angle snow. The fixed ropes are a real help. The sixth pitch was Hank’s lead and he got up it with a lot of difficulty. I was stopped by a short stretch of verglas-coated rock. It just would not go with a pack. The nylon ropes stretched too much to be of use. I try to haul myself up the fixed rope again and again. But just can’t do it. My pack is perhaps 50 pounds. We decide to put my pack on the end of the climbing rope. Then I get up easily but the pack slips down 30 feet and we lose two fixed ropes. I go after my pack but have not the strength to haul it up. By now I am pretty well scraped and bruised. Hank comes down and the two of us retrieve the pack and give up. We downclimb to Camp 1.

Rick, Don and Dave have hauled a second load and Chris and Pete one load to the cache at Camp 1. Chris, Don and Pete are waiting for us there. Chris and Don take our tent, stove and food and camp at the cache and the rest of us return to Base Camp. It had been a disappointing, painful night and Hank and I are exhausted.

June 30

More lousy weather. Heavy mist and rain. That evening, Chris and Don climb to a rock ledge (above the point on the rock face where Hank and I retreated from the night before) without packs. This will be Camp 2. They rig a pulley system from a point 100 feet below the ledge vertically directly above Camp 1. Rick and Dave carry a load apiece up to Camp 1 and help set up the lower end of the pulley system. We use spliced fixed ropes.

Hank, Pete and I strike Base Camp and come up the icefall. The weather is very warm and it is raining lightly. The route up the Icefall is slippery and soft and the crevasses are dangerous. The Cannon is constantly letting go with small avalanches at its rear end and we literally run across the Mouth—for the last time, thank God.

We arrive just in time to help with the pulley system. It works swell and we save a helluva lot of work. We send up 30 pound loads in burlap bags. We have to pull like hell. We use another rope to keep the bag away from the cliff and a sophisticated arrangement of ice axes to snub the ropes. We work all night until only the personal stuff of us five and two tents are left. A productive day. In this manner we raised 800 pounds of gear in six hours.

Shot taken from top end of pulley system. Note how close an avalanche came to our tent at Camp 1 (that tiny red rectangle at far right center)

July 1

Thoroughly exhausted, we pitch a second tent and camp at the cache (Camp 1). Chris and Don pad at Camp 2 on the rock shelf. We have some sweat about rockfall. There are a few near misses and two holes made in the tents. Objectively we are camped in a very dangerous spot. Several rock and snow avalanches just miss us during the day as we sleep. One huge one buries the bottom of our pulley system. And by a miracle I escape unharmed as a heavy rockfall lands all around me as I stand with no place to run.

My diary does not due justice to what was one of the closest calls in a life full of them. Here's how I described it in my memoir, Quest:

"Suddenly I heard the sound of much bigger rocks crashing down the cliff face. Dave had already left the tent to take a leak, and was protected by an overhang twenty yards away. I unzipped my sleeping bag and dove out of the tent into the snow. I got up but it was too late to run. A barrage of rocks, some of them the size of cannonballs, was heading straight for me. I stood there in my thermal underwear, frozen in place, and watched dozens of rocks whistle past my body. They smashed some supplies and equipment, but not one touched me.

"Dave Roberts would become one of America’s best-known mountaineering authors, and in one of his books he describes this incident as one of the damnedest things he’d ever seen. I remember staring up at that cannonade as if in a trance, watching it all in slow motion; I could even make out patterns of color and texture in individual rocks as they flew by, some of them all but parting my hair.

"When it was all over, and the last pebbles had clicked down the face, I stood there silently. We’d all assumed that none of us would die on the mountain, but the odds on my surviving this rockfall had probably been one in a thousand."

Roberts offered this picture in an interview with Alpinist magazine in 2017:

"There were falling rocks that drilled holes in our tent. There was one gigantic boulder that landed and bounced over John Graham’s head. We just thought, “This is cool! This is what big mountains are all about!”...When I look back on it, I think, knowing what I know now, we might well have backed off it if we had better judgment. It was kind of foolish to go up on it. People say it’s never been repeated because it’s now recognized as being dangerous. Yeah! The Huntley/Brinkley report: 'Missing and feared dead.'”

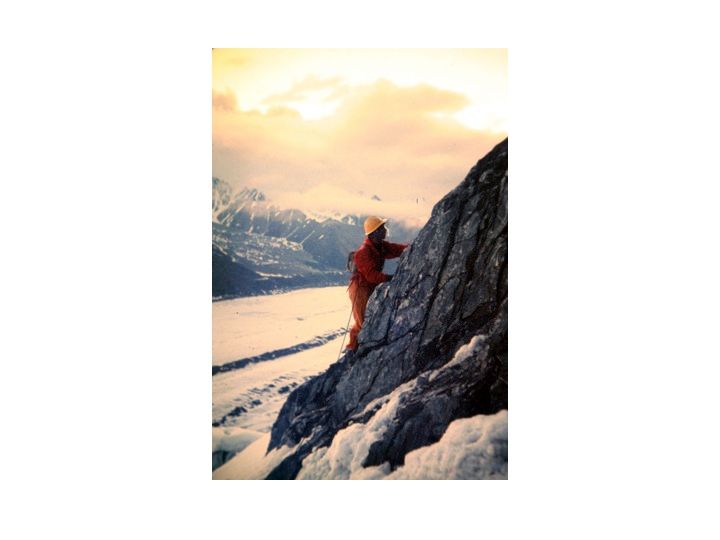

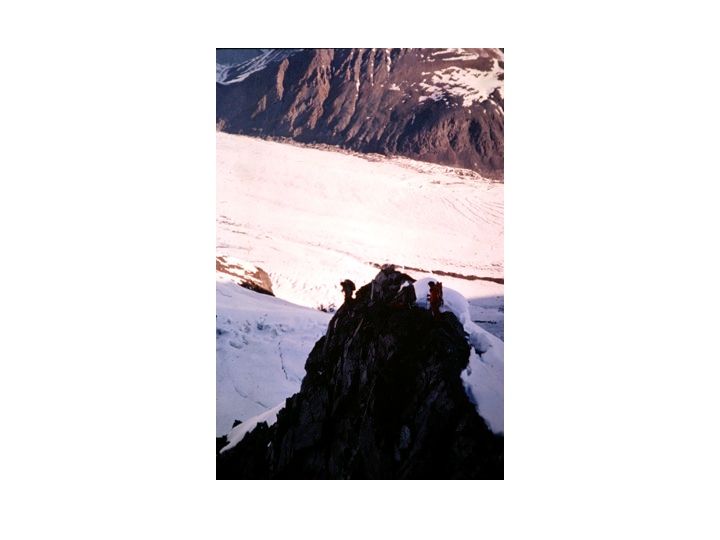

We rise at 6:30 PM and get dinner. Pete’s ax had been lost in a slide but we finally find it. It is two more hours work before everything except we five has been hauled up the pulley system. We all think of all the effort and time this device is saving us. With everything hauled, we strike Camp 1 and climb the route to Camp 2 on the rock shelf. It is colder so the snow is better. We have no packs so we climb up no sweat. We all reach the shelf (7,100’). What a view! We are 1,700’ above BC and for the first time we feel we are on a mountain. The shelf is amply large for a camp site. It is good snow. We haul everything from the pulley terminus up into camp. Meanwhile Don and Chris are hard at work toward Camp 3 which will be placed at the top of the steep rib of rock of which the shelf is a part. The weather is beautiful and the view is tremendous.

CHAPTER FOUR: TOUGH CLIMBING

July 2

We pad until 8 PM and then do odd jobs and eat a big mess of StarLite Chili and Shrimp Creole. Great!

At 11:30 the snow is hard enough for us to move and we all head up the route kicked out by Chris and Don. The route from Camp 2 goes up a very steep snow and rock rib with part of what we call "The Eiger Face" on one side and another precipice on the other.

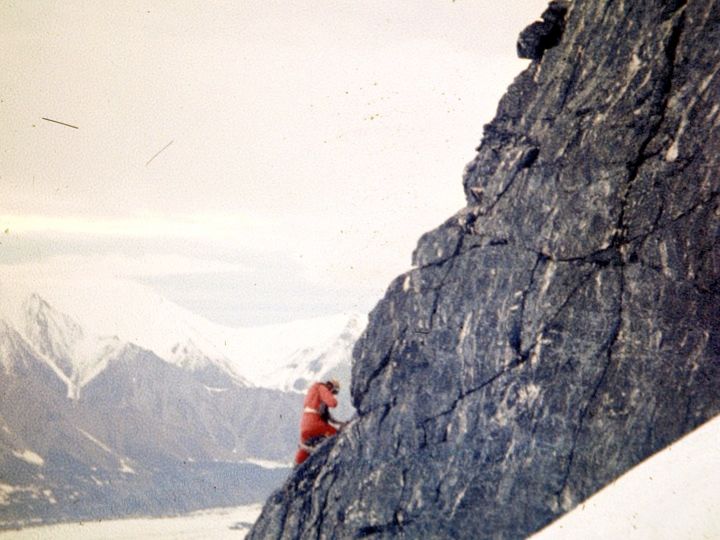

I’m at about 7,500 feet in this photo, looking up at over two vertical miles of climbing ahead. We know there will be difficulties and dangers ahead that we can’t see from here, but we are all in good spirits and confident. After all, we’ve successfully dodged the avalanches in the Cannon’s Mouth, scaled a difficult rock face and built an ingenious pulley system to haul our supplies to its top. Personally, I’ve walked away from the first near-miss I will encounter on this climb. So yeah, I see the difficulties and dangers ahead and I’m sure we have the skills, endurance and smarts to meet them.

I've added here notes from the American Alpine Journal (AAJ) article, A New Route on the Wickersham Wall, by Hank Abrons.

The "stirrup" that Hank refers to in the paragraph below was another ingenious invention for this trip. Essentially it was a rope ladder with aluminum steps we cut and shaped from bars we found in a builders supply store.

From the AAJ: "During the night of July 1 we climbed to Camp II while Goetze and Jensen reconnoitered the spur above. Slightly less steep, nevertheless it posed several problems: rock gendarmes (tall, steep rock towers); a slightly corniced (overhanging), soft, snow crest; and a 70 degree ice headwall encrusted with rotten snow. They progressed as far as the most difficult gendarme, which overhung on two sides and dropped off sharply on the other. The next night Carman and I climbed this using a stirrup; the pitch also involved a strenuous retable which provoked unspeakable grunts the following night, when, with our fellow "sherpas,” we returned to the job of lugging up equipment to keep pace with the advance rope. Happily, everyone was not only an experienced leader eager to take his turn in the reconnaissance party but also a team member dedicated to carrying loads, digging tent platforms, cooking, etc."

Jensen taking a rest above the rock towers

July 3

It is easy going as long as the steps are good. Hank and Pete take personal packs up to Camp 3 on a little shelf at 7,900’ and go on from there to push the route past the First Fluting.* The rest of us spend the entire night moving all the expedition gear to Camp 3 and then return to Camp 2 on the rock shelf. (7,100’)

*"Flutings" are hard snow formations we encountered lower down on the Wall. They were very steep, shaped like a crumpled rug on edge. See picture below

Denali "flutings"—steep ribs of hard snow

Descending to Camp 2

Chris Goetze taking a break

Our first trip up comes just as the sun is rising. What a sight! We get some fine pictures of climbers outlined against the sky with precipices dropping off on both sides. It is great climbing! Three or four fixed ropes previously laid make it even easier. Now we are really moving! Now we are really above something! We can see the McKinley River and beyond. It is an exhilarating and unforgettable night. Everything is going well. The weather is fine and we are all well and in high spirits.

We sleep the sleep of the dead. At 9:00 we get up and get going with another Starlite glop.

July 4

Tonight, Rick and I are the route finders. We take our personal gear to Camp 3, then up to Camp 4 which has been put up just below the Second Fluting at 8,500.'

That's me (bottom left) packing up to Camp 4

Rick and I leave our packs at Camp 4 and take fixed ropes, hardware and pickets and start up. We hit a lot of steep snow and then a technical ice pitch which Rick leads in fine style. We leave a looped fixed rope here. There is more steep snow, then we hit broken-up ice and crevasses. I lead a long stretch of technical ice. We’re really roaring now! We pick our way through towering seracs and piles of snow-cover ice blocks. We get to just below the Big Crevasse, at about 10,300.’ What a view! We return to Camp 4 by about 9:30 AM.

Below are images of the technical snow/ice wall Rick and I led this night. We had plenty of practice with terrain like this from our winter climbs on New Hampshire's Mount Washington.

Packing above Camp 3

Pete Carman and his famous tie

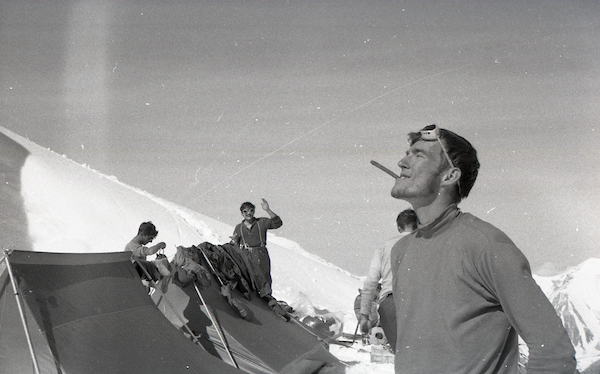

Camp 4 is the scene of a July 4 snowball fight. I break out my cigars. We’re going great. Nothing will stop us now. The weather could not be better. But mountaineering is a lot of work!! These nights are killers.

Hank gave haircuts to our bushier members today. We are now above all the rockfall danger and 90% of the avalanche danger.

Tonight the weather is socked in—a whiteout with gently falling snow. Chris and Dave are the route-finders tonight. They will put fixed ropes into the part of the route that Rick and I led last night. The rest of us head down towards Camp 3. The snow is very soft.

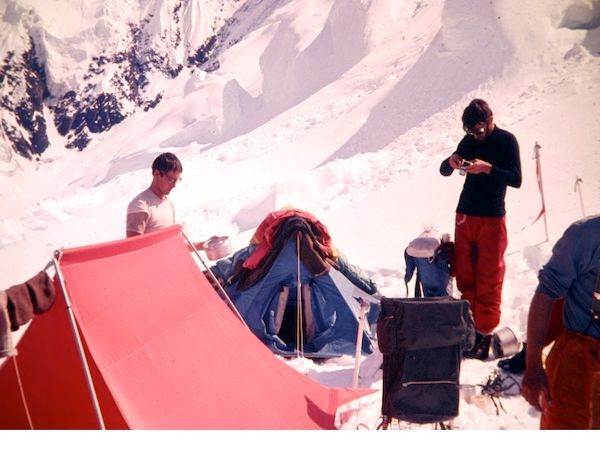

Here are a few scenes from Camp 4. Considering the prolonged dangers, stresses and effort, there was an amazing light-heartedness to this climb. We worked well together and enjoyed each other's company.

Spirits are soaring! It looks like the Wickersham Wall is far easier than we had thought. A couple more night’s work should get us close to the top of the steep section at 14,000.’

Camp 4: We think we got it made!

July 5

A thin traverse we call Shady Lane is really treacherous now and Hank and I both fall on the fixed rope. I am leading on down below when a cornice I am tiptoeing on gives way under my right foot. I jam my ice ax in quick and hang over a thousand foot drop for a few scary seconds until I can haul myself back up. Brrrrr.

We retreat to wait for the snow to harden up. Dan, Rick and Pete eventually go down for two loads and bring some stuff, personal gear and a tent from Camp 4 to Camp 5.

Camp 5 is at about 9,300,’ about halfway up the route that Rick and I did and about 200 feet above the vertical ice pitch where we left the knotted ropes.

Whew! Across Shady Lane

Looking down on Camp 5

Bradford Washburn photo

The above photo shows the middle section of what would become known as "The Harvard Route" up the Wickersham Wall. We climbed essentially straight up the middle.

For Hank and me, the night continues to be a memorable one. We haul two loads from Camp 4 to Camp 5. Then, at about 6:30 AM, we unwisely elect to go all the way down to Camp 3. We meet the other three coming up and they tell us that the two loads left are whopping. On the way down Hank and I are treated to some really spectacular scenery.

The mist has lightened somewhat and the icefalls, seracs and distant peaks look like ghosts. We get down to Camp 3 all right and pack up about 65 pounds each. It is too much for the steep, tricky route from Camp 3 to Camp 4. There are two rock towers to be gotten over first. The first is done easily. The second has a bad stirrup move at the bottom and we have a hell of a time. I break through again and just about go the distance again. We (mostly I) curse and swear and sweat and tug. It is no fun at all. Ropes and equipment get in the way.

We are both bushed after we finally get over the second tower. But now we are on a tight spot. It is almost 11 AM and the clearing sun has made the steep ridge up treacherous. Steps give way. A whole hunk of slope just about takes Hank with it down the Wall. We gingerly haul ourselves up. I am frankly amazed at the stamina we (and the whole group) has shown. I frankly don’t know what keeps us going. It is murder. Physically exhausting and extremely dangerous. We belay all the way up. Finally we inch past Shady Lane and up the final slope to Camp 4 where we fall like dead men, completely exhausted.

That bit was one of the most exhausting and dangerous things I have ever done.I would never want to do it again. It is with the help of God that we made it. But boy do we feel like kingpins for pulling it off!

We rest and eat and drink for an hour. Then we strike the last tent and and take it and our personal gear up to Camp 5. Our loads feel like feathers after that horrible night. I lead the ice pitch like a Sherman tank. Up we go.

We arrive at Camp 5 at 3:30 PM, set up the tent, eat breakfast, and collapse.

Tremendous view from here. The sky above is blue and cloud banks hover on distant peaks. Tremendous. Boy do we sleep.

In retrospect, the night of July 5-6 was arguable the most dangerous of the trip, at least for me and Hank. My diary bravado doesn’t quite describe how unnerving it was to climb across Shady Lane with a heavy pack, with all the steps we’d kicked the day before melting out. Only a few metal spikes on my feet and a ¼ inch fixed rope helped me keep my balance, looking down thousands of feet to the glacier below, every muscle aching from the effort to not fall. Yes, Hank was belaying me from above—from a single aluminum picket shoved into unstable snow. I don’t think I’ve ever concentrated that intensely in my life.

And earlier that same night I will never forget the sound when the entire cornice I was walking on suddenly fell away. The sound was a soft whoosh, like the blowing out of a candle. One second I was supported by the soft snow; the next second I was walking on air, looking straight down thousands of feet as tons off ice and snow fell away beneath me. I had time for one swing of my ice ax at what remained of the cornice and luckily it bit into something solid, just as Hank’s belay rope from above tightened around my waist. “No big deal” we told ourselves. And truth be told, it actually was kind of fun.

And the dice continued to roll, often in unexpected ways. This anecdote, from my memoir, Quest, describes a near-miss at Camp 5:

"We’d pitched our tents on a rare flat expanse of hard snow, protected on the uphill side by a fifteen-foot ice cliff. Late that afternoon, we awoke to start the next night’s climb. Rick crawled out of his tent first, then ambled a few feet ahead and began to pee a hole in the snow. Suddenly that hole got bigger and bigger, as the yellow snow began to fall away into a crevasse so big that he could not see the bottom. We’d pitched our camp on a fragile snow bridge over a monster void. Rick stared, then carefully backtracked to the tents and quietly told us that we could at that moment be pulling on our socks on top of two hundred feet of air. One at a time we slowly and carefully got out of the tents, pulled the stakes, then gently dragged or carried everything out of harm’s way, choreographing our moves to put the least possible strain on whatever supported us. The five minutes it took seemed like forever."

Camp 5. And I still have this hat!

Camp 5 housekeeping

While Hank and I were having our exhausting night, Chris and Dave were putting more fixed ropes in the upper part of the route Rick and I had blazed above Camp 5 and then they continued up. They encounter a huge ice cliff at about 10,300’ but find a relatively easy way up it by climbing through a vertical cleft or chimney we call “The Icebox.” They establish a cache and a tentative site for Camp 6 just above that ice cliff at about 10,400.' They return to Camp 5. We all sleep in until midnight since we’ve had such an exhausting time of it.

The ice cliffs still tower above us

Approaching ice cliffs in blowing snow

Getting colder up here

At aboit 10,300

Rick Millikan just below the ice cliffs

How are we going to get over THAT?

And THAT?

And THAT?

Navigating the ice cliffs

Picking our way up steep snow and ice

The snow and ice formations were wierd

And weirder

The shots below show how we found a relatively easy way up through the last of those fearsome ice cliffs: We called this cleft in the ice wall, "The Icebox."

Approaching "The Icebox"

Millikan atop "The Icebox"

This is the end of Part One. Read on by returning to the Nav Bar and clicking on Denali Diary Part Two